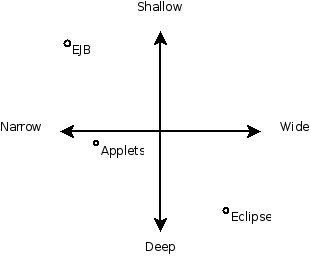

Dimensions of software frameworks

This past weekend I was chatting with Ciera Jaspan about her work on frameworks. We chatted about Bill Scherlis’s observation that framework interfaces are wide, while traditional library interfaces are narrow. As I mentioned briefly in a prior blog posting There is another difference you see in frameworks — some interfaces are deep, others are shallow.

In saying that frameworks have wider interfaces than libraries, Bill is saying that a client program using a framework interacts with many framework objects, unlike a library where you would typically interact with just one object. The second dimension, deep vs. shallow, addresses how deeply the client traverses into the data structures. In Eclipse, for example, you often find code like this fictitious example:

parent.getWorkbench().getMenuManager().getToolbar().add(myNewItem)

Let’s call that deep, since it allows the client to dig deeply into the data structures exposed by the framework. Shallow interfaces would expose a limited set of objects to the client, perhaps just one level.

These dimensions become interesting when you ask “How can I design my framework to be comprehensible by mortals?” The closer your framework is to the top left (narrow + shallow), the easier it will be for developers to understand and use correctly. You can think of two competing forces: One pulling to the bottom right (wide + deep) because it’s easier for framework writers to build and requires less up-front planning, and one pulling to the top left (narrow + shallow) which is easier to use.

There is lots of hype today about Service Oriented Architectures, and there has been longstanding interest in making software services available remotely using remote procedure calls, CORBA, RMI, etc., but this is hard to do with deep + wide framework interfaces. Of the two, deepness is harder to enable remotely. Consider the fictitious example above, and realize that it would translate into four remote calls. A shallow interface would require fewer remote calls, or even just one.

The wrong way to interpret these insights would be to assume that all frameworks should be narrow and shallow, and that it’s just ignorance and laziness of framework writers that has given us wide and deep frameworks. Instead, we should try to develop heuristics to guide the choice for framework writers, because some domains will be amenable to the narrow + shallow frameworks (like EJB), while other domains may require either interfaces that are deep, wide, or both.